1Notebooks Now! Initiative Evaluation

Towards an open compuational notebooks publishing ecosystem

Abstract¶

This report summarizes an evaluation conducted in late 2024 of the AGU Notebooks Now! initiative, focused on its openness. Computational Notebooks are documents that combine natural language with programming code and the results of the code’s execution in a single file. Examples include Jupyter and Mathematica Notebooks. My assessment is that Notebooks Now! is a solid foundation to build publishing systems that include computational notebooks as first-class objects for peer-reviewed scholarly publishing. The work completed so far provides open source tools for scientists to author notebooks aimed at peer-reviewed publishing, is based on openly documented standards and approaches, and creates no undue barriers to competition nor locks key functionality behind specific vendors or proprietary services. A list of open resources resulting from this initiative, as well as recommendations for future work, are provided.

2Scope and executive summary¶

This document reports on my discussions with the AGU and Curvenote teams working on the current Notebooks Now! prototype infrastructure. The information here is based on three one-hour discussions with Brian Sedora and Shelley Stall from AGU, and Rowan Cockett from Curvenote. My goal was to answer the following question:

Are the publicly available outcomes of the Notebooks Now! initiative a good foundation for open pipelines to publish computational notebooks as academic, peer-reviewed literature? Specifically, I looked at whether all tools and processes created or proposed would be sufficiently open for scientists to use, build upon and modify, and for others to potentially create new efforts in this ecosystem, without any artificial barriers or lock-in that could favor a particular vendor or organization.

In brief, my conclusion is: to the extent I was able to ascertain in this limited audit, and as per the above goal, I found no evidence of barriers, blockage or undue favoring of any particular vendor in the currently developed tools, documentation and plans. While clearly AGU (and their publisher Wiley) as well as Curvenote have in-depth knowledge of the project based on their own work and participation, I didn’t identify any areas where this would create artificial barriers to independent (community-driven or commercial) efforts for alternate publishing mechanisms and projects, or to the workflow of practicing scientists who seek to author and submit compatible documents.

Furthermore, the teams demonstrated that these tools can be used to create rich, interactive publications with all the necessary elements of a scientific paper (equations, tables, figures, bibliographic references, etc.). These can include both rich, modern and accessible HTML, and graceful fallback to static PDF. They can also link to executable environments for reproducible execution of the analysis in the publication. These have been demonstrated both with real-world publications from AGU authors, and in a fully open workflow for the proceedings of the annual SciPy conference. See Sec. 4 for details.

Finally, I note that this document focuses only on the implementation of tools in the Jupyter/MyST ecosystem[2]. The Notebooks Now! initiative also included participation of members from the Quarto ecosystem. I did not evaluate that toolchain, however I note that Quarto developers also contributed to common documents and specifications, helping harmonize the workflow for all implementations (links and details provided in Secs. 3 & 4).

3Context: open science and scholarly publishing¶

Scientific publishing is a complex ecosystem where a mix of researchers, professional organizations, non-profit entities and commercial vendors all participate. The focus of my audit was to ascertain that we will be able to move towards a future that includes computational notebooks as part of the published record, where:

Researchers can create notebook-based content and submit it for publication, using 100% open source tools that they can use locally or in the cloud, and that do not require support or services from any specific vendor.

Existing publishers can consider accepting such content by relying on openly documented standards and implementations.

New actors can consider developing new publication models and journals based on these tools, without being at an undue disadvantage.

Importantly, this does not mean that the entire end-to-end toolchain used in commercial publishing was meant to be open sourced. That was never part of the scope of the Notebooks Now! effort, and I recognize that AGU, Wiley, Curvenote and their partners may have developed proprietary tools as part of their publishing activities. These will continue to exist.

My focus was only on ensuring that scientists could have a clean field for creating notebook-based publications without any proprietary bottlenecks, and that for anyone wanting to work on the publishing side of the problem, the playing field would be open and fair. Obviously such efforts may require publishing competitors to adapt their existing systems to these new formats or build new tools. I only looked for any artificial barriers that would hinder such open competition in the marketplace.

4The notebook publishing workflow¶

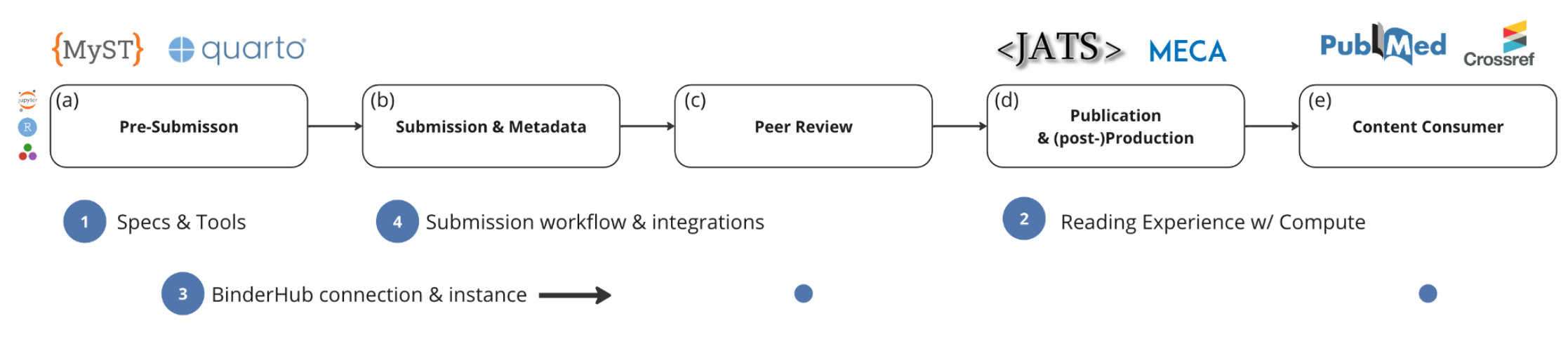

Figure 1:Outline of steps in the workflow for publishing notebooks, with key tools highlighted at various steps in the process.

In Figure 1 we see a high-level outline of the steps in the authoring and publishing workflow prototyped during the Notebooks Now! effort. In this system, the following parts were developed with fully open source infrastructure and implementation:

Submission templates for authors, as described in the MyST documentation.

Continued standardization of the JATS/MECA for notebooks, as described in Science Communication with Notebooks. This working draft was co-authored by industry and scientific community members, published under CC-BY licensing terms. It contains the authoritative reference on these ideas in a vendor- and tool-agnostic way, as it covers both the MyST and Quarto implementations and had contributions by authors from both ecosystems.

Publicly available submission instructions for authors to use the AGU templates for Notebooks Now! submissions. Developed by Curvenote, the instructions live in a public Github repository that others can contribute to.

Incorporation of publishing-specific metadata as defined by the metadata working group, also detailed in the above Science Communication with Notebooks.

New MyST themes and templates, that include specific themes for scientific articles and books. There is a dedicated Github organization for MyST Templates, that makes it easy for the community to grow the ecosystem of available templates and improve existing ones.

Two important parts of this diagram currently remain proprietary; neither of these was in scope for my assessment, nor did I have any visibility into them:

The Curvenote Submission System: this is technology developed by Curvenote that supports submissions into their systems and journals.

Integrations with Wiley: this is part of AGU’s existing publishing system, as Wiley is the publisher of AGU’s current journals.

Both of these include their own tools for peer-review, an obviously key part of any publishing pipeline. While the specific implementation of peer-review workflows in Curvenote or Wiley journals may be proprietary, the community workshops of the initiative provided extensive input into what the needs of various stakeholders would be to ensure the most open and effective process possible.

As noted above, the existence of these proprietary components is consistent with the scope of the Notebooks Now initiative; I flag them here for completeness of this evaluation. I hope and expect that, as part of the growing ecosystem of efforts to develop alternative models and workflows for sharing and publishing scientific content, the open parts of this initiative will both be integrated into those efforts and will spur new ideas and tools.

5Key resources and results from the Notebooks Now! initiative¶

The following summarizes key outcomes and resources resulting from this effort[1]:

Main Notebooks Now! site: official website for the initiative.

Science Communication with Notebooks: key document listed above, co-authored by industry and scientific community members, published under CC-BY licensing terms. This is the authoritative narrative of the main publishing-oriented ideas, definitions and technology in this effort.

MyST Markdown site: while MyST is a broader open source effort with its own community and goals, the Notebooks Now! initiative led to many important improvements to MyST, and they are all documented on the core project site, ensuring the broadest reach possible.

Published articles showcase site: this site shows how a few (manually curated) real-life scientific articles from AGU disciplines look like when published with this toolchain.

Proceedings of the Python in Science (SciPy) Conferences. Similar to the above showcase, but instead of a manually curated demonstration of AGU science, it shows the use of these tools for a real-world conference where the organizers (with Curvenote’s support) adopted them to publish the complete set of proceedings. Importantly, and as a demonstration of the power and flexibility of the toolchain, the team not only used this toolchain for the 2024 proceedings, they were able to also convert the 2022 and 2023 ones to this format, as well as offer a full archive of all former abstracts dating back to 2008, that includes for each older abstract a link to the static PDF generated with previous technologies.

6Conclusions and recommendations for further work¶

As summarized in the abstract (and hopefully supported by the details in this report), I see Notebooks Now! as an excellent foundation for the development of an open ecosystem for including computational notebooks in the scientific record. I hope this initiative will capture the excitement around these ideas that was palpable during various activities at AGU 2024, and the interest that has been expressed by members of other scientific disciplines, and that in 2025 and beyond this moves from the early prototyping stage into broad, real-world adoption.

Plenty of work remains to be done in many areas, and real-world usage will quickly show areas that need improvement. Some areas where I hope to see progress are:

Peer review: as indicated above, this initiative didn’t really focus on producing any new tools for peer-review. I hope open efforts from different organizations and disciplines, who have existing tools in that space, will explore how to best integrate them with notebook publishing.

Archival: best practices and approaches for long-term archival of notebook-based content, that take into account graceful degradation to PDF as well as the longevity of complex web technologies, are still in their infancy.

In-depth testing of the complete end-to-end workflow hasn’t yet really happened, and it is likely to uncover many rough edges and limitations of the current prototypes.

Work to nucleate action from others beyond AGU; I see a lot of potential by including other scientific societies with aligned interests, that could facilitate adoption of these ideas across scholarly publishing.

Based on these, I suggest (with adequate further funding and support), the establishment of working groups on at least peer review and standards/archiving, as well as a coordination group for early adopters across scientific societies and publishers, to tap into the potential for usage in other disciplines.

Finally, I recommend that the Notebooks Now! team gather some of the documentation and materials that were created during the development of the project. The resources listed above are extremely valuable, but a public archive of documents created by the various working groups would be an excellent complement to these, even if those are in less polished form.

7Disclosures¶

The Notebooks Now! initiative drew inspiration from the role of Jupyter Notebooks in science. I am a co-founder of Project Jupyter and have held various leadership roles in the project: during the work summarized in this report I served on its Executive Council, which is a volunteer position. I hold no stake in Curvenote Inc. I was not compensated for this assessment and I have done it as part of my professional service to the scientific community.

Colophon: this document was authored using MyST and JupyterLab. PDF output was generated by the LaPreprint-Typst template.

Acknowledgments¶

I am grateful to Shelley Stall and Brian Sedora from AGU, and Rowan Cockett from Curvenote, for their time and openness during our discussions. All three were provided an opportunity to see my draft of this report before I finalized it, to provide input on readability and correctness. Its conclusions and editorial decisions remain my responsibility. I thank Chris Holdgraf for helpful feedback on earlier drafts; all errors and ommissions are mine.

MyST, short for “Markedly Structured Text”, is an extension to Markdown aimed at scholarly publishing, originally started by the author ca. 2017 as a simple specification that combined the syntax of Markdown with the programmatic extensibility of Restructured Text. This simple spec was then developed with funding from the Sloan Foundation by C. Holdgraf, J. Stachurski, G. Caporaso and the Executable Books team, leading to a Sphinx plugin in Python used by JupyterBook v1. Starting in 2020, R. Cockett and the Curvenote team created a new, modern TypeScript implementation that built upon the MyST specification, and introduced a formal document structure and engine for reproducible publishing. This new document engine used modern web technology, and could operate both in a live JupyterLab session and at the command-line. It also combined the MyST specification with an engine that could generate HTML, PDF and other outputs. This implementation was contributed to the community by Curvenote as open source and is today the official MyST distribution; work to integrate and further develop this new open source project was also funded in-part by the original Jupyter Book grant. MyST will be the engine for JupyterBook v2 (now an official Jupyter Subproject), replacing Sphinx and the previous Python plugin.

The team at Posit Inc. also contributed to the authorship of some of these documents and made corresponding improvements to the Quarto toolchain; I link to it here but I did not specifically look at their architecture, nor met with their team, as part of this evaluation.